This time, when my Fitbit thinks I’m swimming, I’ve been sliding my arms in and out of summer tops to see if they still fit—metaphorically swimming, perhaps, against the currents of aging. It’s a ritual that thins my closet, even if it does little to send my body on the same trajectory.

A couple days earlier, when the device registered swimming, I was maneuvering my kayak around downed trees while exploring a creek, pollen spores coating the water as if the universe poured flour into its mixer too quickly, pale dust erupting from the bowl.

As is often true the first few times I paddle each spring, my shoulders started aching. Ow, I thought. Then, thank you, grateful to be on the river—and moving.

My Fitbit is relatively new, replacing a similar Garmin I wore for four years. What sunk in after that second misregistered swim was the option to scroll past aerobics, bike, and walk, and click MORE to unlock a lengthy A-Z activity list. Among them: kayaking and dance (a better choice for the class I take at the gym than aerobics).

How often do I let listed options limit me or select a frequent or familiar choice without taking the time for an extra tap and scroll (literally or figuratively)—or to imagine an unlisted possibility?

Lately, I’ve been pondering the power of lists and categories. I’m not sure whether it’s the White House’s callous campaign to erase certain categories from our collective lists that has heightened my awareness, or if there are other contributing factors, but I’m noticing them everywhere.

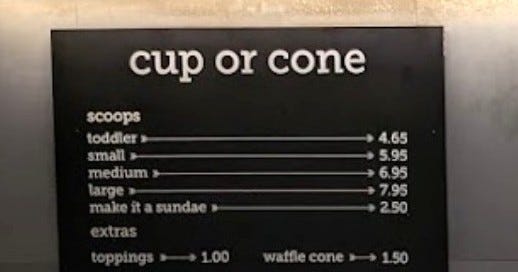

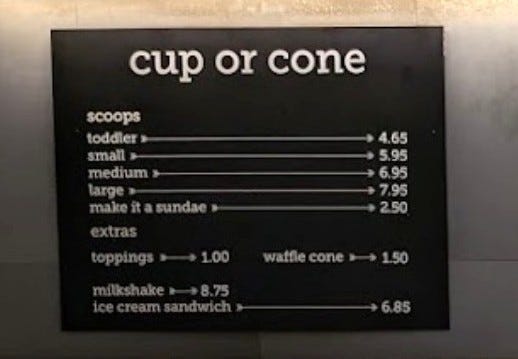

Consider the menu at our local gelato shop where a small contains two scoops, a medium three, and a large four. Want just one scoop? That’s called a toddler. It’s a size I sometimes order, but it feels weird whenever I say it aloud.

Imagine a kid who just learned to read, who’s starting to think of themselves as a big kid. How likely are they to gaze up at that menu and ask for a toddler-size scoop? How do such options influence consumer behavior or cultural values?

When I scrutinized my activity tracker, I noticed similar layers.

Ostensibly, such devices get us to move by drawing our attention to steps or other stats. I focus on active zone minutes. Each week, I strive to double the standard 150-minute goal, hoping to reduce my risk of ailments associated with sedentary behavior: cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, and colon, endometrium, and lung cancers (Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition 45).

But what specific kinds of movement does the Fitbit menu include?

Prevalent on the list are gym-based classes like CrossFit and HIIT, costly exercise machines like ellipticals and treadmills, and outdoor activities that require substantial special equipment, such as golf, skiing, or paddleboarding. Even though I racked up 132 active zone minutes doing yardwork recently, physical exertion associated with work or chores is missing from the list.

Thus, such devices applaud spending leisure time exercising, particularly if that exercise requires a gym membership and/or purchasing special equipment. What if you’re a person without much discretionary money in your budget? You could choose dance, hike, run, or walk, but how might it feel to scroll through a 40-item list and see 30 activities you can’t afford to do?

On the other hand, how might it feel for someone with an active job like nursing, waiting tables, or packing boxes at Amazon to earn an “active work champion” badge if they clock 300+ active minutes or walk 20,000+ steps on their shift? Such step counts were an everyday occurrence for my aunt when she worked at a diner.

To catch activities that don’t make the list, there are three generic categories: outdoor workout, workout (presumably indoors) and sports. There’s no option for play. Does this absence suggest that play is not an appropriate option for adults, or that we should seek structure and competition in our leisure time? Since most sports involve fees, it’s also another nudge to spend.

I noticed something else too. Few activities on the menu require cooperation or two-way communication. Solo exertion is the focus—or following the directions of an instructor (maybe human, maybe AI) without engaging directly with other participants. Ironically, you can share stats from your alone or alone-together movement on social media. Wouldn’t people feel more connected if they engaged in exercise, active play, or active work with those friends or family members?

Isolation is as dangerous to our wellbeing as being sedentary. In 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a report raising the alarm that feelings of loneliness and isolation among Americans had risen to epidemic proportions. How might an activity tracker (or an associated app) do more to affirm free or low-cost exercise, active work, or active play that’s social instead of solo?

Is it unreasonable to expect something more like a Wellbit? I don’t think so. The option to track meditation and sleep (more things many of us do alone) on several popular activity trackers suggests that their designers understand human wellbeing encompasses more than exercise.

Then again, if someone invents a Wellbit, maybe it would cost more than I’m willing to pay. In the meantime, I’ll wear my Fitbit or something similar. It’s more affordable than a smartwatch and allows me to track steps and active zone minutes while leaving my smartphone behind, less screen time among the unsung benefits of such devices.

The third time my Fitbit thinks I’m swimming, I am. It’s my first time going to the gym at 7am on a Saturday, and I’m surprised by how many people are in the pool, each of us in our own half-lane (no connect-with-people points for me). When I walk back to the locker room, I notice the available categories: women, men, and a few separate rooms in the middle labeled for families. Would someone who’d prefer to change in a middle space but who doesn’t have a child in tow feel welcome to do so?

As I climb into my truck, I mentally add swim to my “done list,” a practice I learned about in Oliver Burkeman’s Meditations for Mortals. That night, before going to sleep, I say a silent prayer, calling to mind specific things I’m thankful for from that day—like access to a pool. I cultivated this gratitude habit years ago (something I’ve written about in more detail before), a simple list that fosters a sense of abundance, even on days filled with disappointment or sorrow.

Attention. It’s why lists and categories matter. All sorts of organizations and people craft lists, menus, forms, and signs to guide our attention and behavior. The words on such lists, as well as words left out, shape the messages conveyed. We can tap into the power of lists too, redirecting the lens of our attention by making our own…

This week, tune in to the lists and categories you encounter or wear. What or who do they include or omit? What values, behaviors, or beliefs do they reinforce, discourage, or complicate? What feelings do they spark? What kinds of lists do you create? Why? Consider sharing something you notice by adding a comment below.

Here’s a poem for your pocket until the next post: Self-Elegies, a deeply moving poem by Martha Silano in which she mentions both a fitness tracker and a birding list. It was written during Martha’s struggle with ALS. She died a few days ago, and although she’d been publishing for decades, yesterday was the first time I’d read her poetry—when I clicked on a link from a student. Last night, that student and Martha’s poem were in my gratitude prayer.