From Anxious to Generous Frugality

How a shift in my relationship with money relates to gratitude, retirement, and joy

When my wife Annette read my last post, she asked, “How would that make money?”

“I doubt it would,” I replied, smiling, “but it might make a difference.” She smiled back, shaking her head.

Monetizing is not my strength. I enthusiastically dive into the doing but turning an idea into an income stream? It’s like my brain hopscotches right over that part of the planning.

Like many educators, I’ve had my share of side hustles—even got bank accounts and business cards for two of them. Although I enjoyed them, both ventures fizzled. The first, which centered on research and tech teaching during Google’s early years, fizzled after I took an adjunct teaching gig in addition to my library position. The pandemic derailed the second (which I provided a glimpse of in my last post).

As I contemplate what to do next (likely within the next five years), Annette’s question matters. At a minimum, the path I pursue must provide health insurance or generate enough income to pay for my health insurance (Annette’s covered by Medicare and a supplemental, so she’s OK there).

Hold on, you might be thinking. If you waited to retire until you’re eligible for Medicare, most of your insurance costs would be covered too. True.

But you know how women who want children sometimes say they can hear their biological clock ticking? I hear the ticking of what poet Mary Oliver calls my “one wild and precious life.” The age gap between me and Annette intensifies its tempo. I’m not willing to wait until I’m 65 to try a different way of making a difference.

I’m lucky. As a public educator eligible for a pension, I’ll have a decent baseline. Annie, who transitioned to a simpler, nomadic lifestyle eight years ago (which she writes about on Wynn Worlds), mentioned jumping without a safety net in her response to one of my previous posts:

Yes, I had to cobble together some part-time contracts and learn to live on less, but what I’ve gotten back in return has been worth it. Sometimes jumping without a net (or a cape) is worth the risk, just to challenge our aging selves to realize we can start over, we can change paths, and we’ll be just fine.

We’ll be just fine. With all the dire warnings about how many millions we should have in the bank before we retire, that can be hard to believe.

Several years ago, after a long stretch when I couldn’t stop worrying about money, I settled on my own version: we’ll figure it out. It happened sometime around 2011. I’d divorced amid the Great Recession and was upside down on the house I’d purchased afterward. At school, positions had been cut and salaries remained frozen for the third consecutive year. I had trouble sleeping.

My grandparents’ generation lived through the Great Depression, and Pop kept a poem folded in his wallet that he often read aloud, the paper feathery. It was an anonymous poem he’d clipped from a newspaper long before I was born.

The Crust of Bread

I must not throw upon the floor

The crust I cannot eat;

For many little hungry ones

Would think it quite a treat.

My parents labor very hard

To get me wholesome food

Then I must never waste a bit

That would do others good.

For willful waste makes woeful want,

And I may live to say,

Oh how I wish I had the bread

That once I threw away.The rhyme and its lesson stuck (two of its verses emerging in a poem I wrote years later). I’ve remained frugal, aware of each dollar and meal. But this was something else. My mind kept drifting to future financial catastrophes like a bowling ball thudding into the gutter. It wasn’t healthy.

And my anxiety was out of proportion with my reality. I had so much to be grateful for. I had a good job (even if it was harder with no book budget) and a home. Most importantly, I was loved and in love. My family lived nearby, and Annette and I had met a few months after I became solo again. We fell in love and spent 18 months living five hours apart, then she moved to Richmond, and we got married (in our church’s eyes, anyway).

I started a gratitude practice.

Each night, I began giving thanks to the universe for specific moments I was grateful for that day: goldfinch flickering on a riverbank, a lesson that worked, a favorite song on the radio on my drive home, the warmth of Annette’s embrace, the taste of dark chocolate with ginger. This stream of positive thoughts was like a bumper rail for my catastrophe-prone mind.

Something else changed too. I’d been tuned to a single story about retirement from financial advisers, colleagues, and friends. Articles and websites reiterated it. The narrative abounds with retirement calculators that project how much savings you need to live on a particular income (usually 70 to 90% of your current income) in retirement. I knew folks who’d banked well over a million who fretted about what ifs and kept working past when they’d planned to retire so they could put more away. As I listened, I worried I could never save enough.

Then I looked back two generations. I come from people who work. Hard. Among my relatives who retired from full-time work before they died, some lived on Social Security alone, some on Social Security and a part-time job. Others had military or state pensions, savings bonds, IRAs, or CDs. A few held onto rental properties. Some lived in a paid-off home, others in apartments (some subsidized), some with relatives, and a few, briefly, in retirement homes. Their lives weren’t luxurious, but for the most part, they were (or are) happy. They figured it out. I could too.

Imperceptibly, over about six months, a knot inside me loosened. My circumstances hadn’t changed, but I began spending less time rolling down the what-I-might-lose gutter and more time noticing my hands on the ball, my feet on the floor, and the friends and family beside me.

Soon, my frugality took on a higher purpose: generosity. As I prioritized sharing my money, I considered how I could motivate myself to stretch past my comfort level. Checklists came to mind. I’m one of those people (maybe you are too) who makes a chore list at 9AM that includes tasks I’ve done since 7AM—just so I can check them off. This didn’t lend itself to a checklist, so I set a lifetime giving goal instead.

I also adopted a giving guideline a friend shared in the context of church stewardship: give until you feel it. In the years since, I’ve found truth in his words. When I skip or delay something I’d like to do or bypass something I’d like to buy so I can give more to build beloved community, my giving feels more meaningful. It also heightens my awareness of the “we” in Annie’s “we’ll be just fine” or my “we’ll figure it out.”

I don’t know if I’ll reach my giving goal while I’m alive, but the journey toward it brings me joy. Really. Not long after these changes took root in me, we were watching TV and the number for our public radio station’s membership drive scrolled across the screen. I leapt up and ran to the phone (we had a land line then), exclaiming gleefully, “It’s time to renew my pledge!” Annette laughed and shook her head, surprised by my enthusiasm.

To have more money to give away or save, I strive to spend less; we both do. Yet, we’re not miserly or miserable. We walk near the river, gather for game nights with friends, pick up takeout or eat dinner out about once a week, and see an occasional play or show. Bigger expenses like vacations take longer to save for than when we kept more money for ourselves, but we’ve adjusted. And when we get to wherever we’re going, we enjoy spending what we’ve saved.

These priorities are a choice, so I don’t begrudge friends, family, or colleagues with millions in IRAs, 401Ks, stocks, or other financial instruments. Most will need to rely more on their savings because they won’t have a pension. That’s one of the financial tradeoffs I made when I left a corporate job: giving up a higher salary but gaining the peace-of-mind of a built-in baseline for retirement. Some friends, if they read this, might worry. But the relationship I’ve settled into with money aligns with who I am and where I’m from—and it expands my sense of abundance. I’m grateful for this shift.

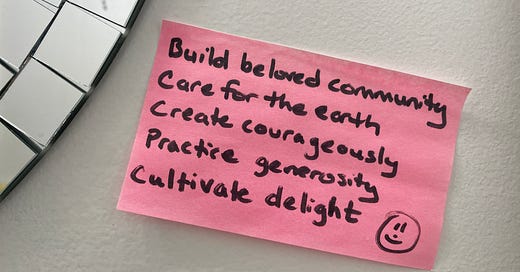

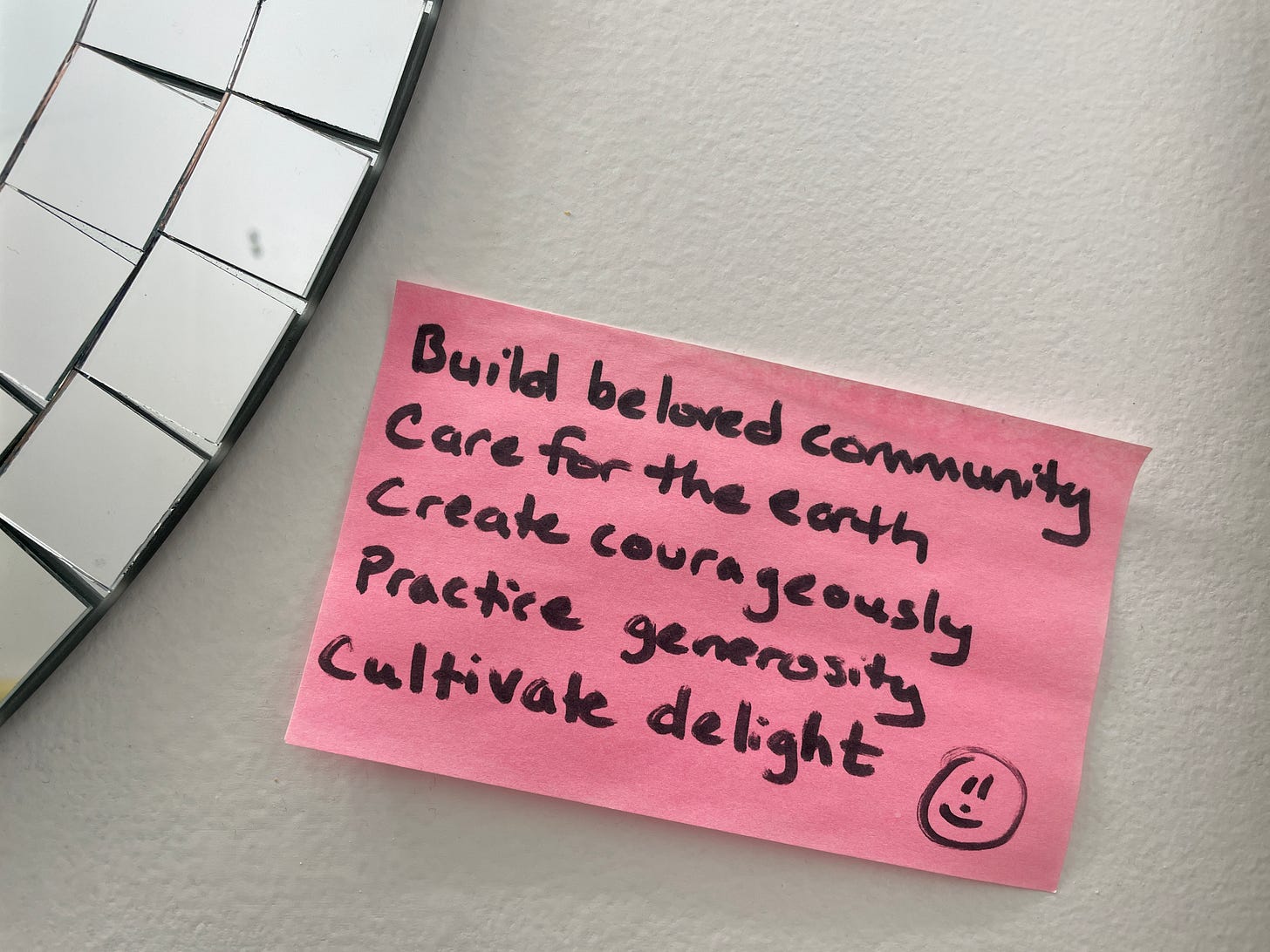

I plan to keep working after I retire from public education. How much money will I need to earn? Annette and I are in the process of figuring that out. Our marriage is the central “we” in my life. We discuss our finances regularly, but now that this transition is getting closer, we need to delve deeply into this question. As we do, we’ll look to the core intentions we developed to guide such decisions. “Practice generosity” is one of them.

Before you go, here’s a poem to tuck in your pocket this week: “Zen of Tipping” by Jan Beatty. Since connecting people with poems delights me almost as much as reading and writing them, I plan to share one at the end of each post from now on. Perhaps some will be seeds for one of your furrows or tinder for your fire.

I’m honored to have been referenced in this post, Wendy. There were two things I didn’t really get “instructed” in when I was growing up for working for a living: (1) how to manage money wisely and save for retirement and then (2) what to do to make retirement, and the rest of my life, meaningful. I think that post-it note you shared is so wise - and good guidelines for your eventual retirement.