Skin hunger and love notes

Considering the role of romantic gestures and platonic touch in human connection

Skin hunger. Before I read Melissa Febos’s essay “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” (from her book Girlhood), I’d known its ache but hadn’t heard the term.

Living solo after my first marriage ended, I remember how the absence of everyday touch amplified the appreciation I felt each time a friend hugged me, or each time I saved up enough to get a massage. How, along with my neck or back muscles, my breath eased on that table and inside those hugs, touch making me feel more grounded and connected, less alone.

During the years I served on my church’s lay pastoral care team, I often sensed when I visited congregants that a hug (with their consent) often meant as much or more than the time spent discussing their struggles, hopes, or fears. Febos suggests skin hunger contributes to depression. That feels true.

Shortly after reading her essay, a headline bobbed to the surface of my news stream about the decrease in romantic entanglements among teens. While 76% of Gen X respondents to a 2023 survey said they’d had a romantic relationship in their teen years, only 56% of Gen Z adults had.

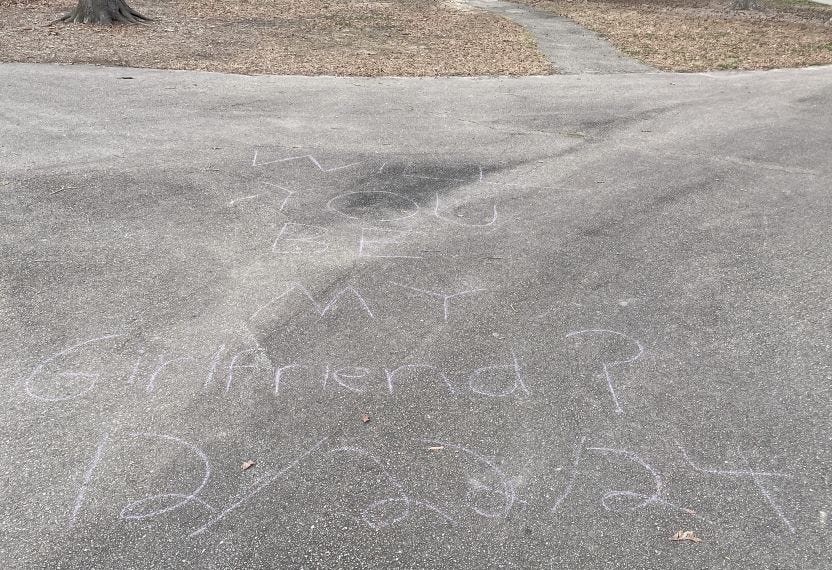

That same week, on a walk at a park behind a high school, letters on the pavement near the playground stopped me. Here, someone defying this trend had knelt on the blacktop and chalked “WILL YOU BE MY Girlfriend?”

You go, romantic you, I thought, grinning as I imagined the butterflies fluttering inside them as they wrote, chalk dust clinging to their hands or gloves, cold seeping into their knees. The fact that no one had returned to scrub the question away, words still visible almost three months after the 12/22/24 beneath it, suggested a yes, or at least that’s what my romantic heart chose to believe.

I first fell for romance in fourth grade.

It happened during recess at Frankford Township Elementary. Even though I no longer recall the name of the shy boy who gave me a gold-colored necklace with a peanut pendant, I remember the wide field where my friends and I played Charlie’s Angels, and the warm fuzziness I felt as I held the necklace, both the boy and me gazing down at our sneakers. I’m not even sure we held hands before my family moved away. But someone wanted to be my boyfriend, and that was new. I would be out of college before I met my first girlfriend.

A decade ago, when students introduced me to terms like cisgender and nonbinary, they taught me another term too: aromantic. When I asked a few who identified as aromantic what that meant for them, they explained that they valued human connection, but passionate love and all its trappings held little or no appeal. Rejecting prevalent cultural messaging that prizes romantic love over platonic love, they chose to invest their energy in close friendships.

Whether or not they consider romance desirable, strong friendships bode well for students’ futures. A 2019 study found that close friendships in adolescence correlate with romantic-life satisfaction in adulthood. Early romance didn’t have the same correlation. Yet there I was, standing beside those chalk letters in the park, cheering for romantic love.

It’s easy to forget that satisfying skin hunger, at any age, requires neither romance nor sex. In fact, the central experiences that anchor Febos’s essay are two cuddle parties she attends, gatherings that provide a structured, rules-based space for consensual platonic touch. Yes, cuddle parties. I looked them up, but this introvert won’t be adding them to my bucket list. If group settings aren’t your thing, a quick search could turn up a business in your area that offers cuddle sessions you can book just like a massage or pedicure. Who knew?

If the exchanges I see in the school library and common areas are any indication, platonic touch abounds for many high school students—greeting each other with enthusiastic hugs or slaps on the back, sitting close while they work or chat, and holding each other when they’re upset.

Thus, when I read about the 20% drop in romantic relationships among teens, it wasn’t touch deprivation that worried me. Instead, it was the imagined absence of romantic love notes in their lockers or backpacks. Those melted my heart when I was a girl and still do. The thought of young people graduating from high school or even college without knowing how it feels to receive such notes makes me melancholy.

But maybe they don’t see it that way. Maybe affirming notes from their friends or family provide their pick-me-ups. Maybe their creative endeavors, intellectual pursuits, community involvement, or other ways of engaging with ideas or people fill them with a fire that warms and holds them.

Then again, some researchers posit that this decline in teen romance is part of a larger struggle with vulnerability and risk among young people and find that they experience higher rates of loneliness than older generations. Among Gen Z adults, 24% reported feeling lonely “always or often” over the 12 months that preceded one study, twice as many as the 12% in Gen X (2023).

Which trends are true for my students? For my niece and nephew, both in Gen Z?

Prom season is just around the corner. Many students attend in friend groups now, but the runup to this springtime ritual is sprinkled with students asking each other to the dance, some quietly, others with grand gestures accompanied by posterboard, glitter, or flowers. Peers often stop their lunchtime conversations to watch, bursting into applause when there’s a yes.

When such scenes unfold in front of me, I start smiling long before the posterboard unfurls. This spring, I’ll strive to heighten my awareness of who might be feeling left out or invisible too.

As a member of Gen X (born 1965 to 1980), I also want to stay open to what I can learn from Gen Z (born 1995 to 2010-12) and Gen Alpha (born 2011-13 to 2024) about the shifting landscape of relationships, to listen more and make fewer assumptions.

That wick lit inside me in fourth grade continues to glow. Despite all I’ve learned since about the ups and downs of romance, I’m still smitten, delighting in every unexpected love note left beside the coffeemaker or on my pillow, each like a dark chocolate, cappuccino, and hug rolled into one.

Here’s a poem for your pocket until the next post: Touch Me by Stanley Kunitz, a Pulitzer-Prize winner who served as the U.S. Poet Laureate twice, the second time at age 95. That same year, I heard him read this poem at the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival in Waterloo Village, New Jersey, a reading that made me teary then and when I watched it again on a Poetry Everywhere video that captured those minutes (among the many reasons to support PBS). As the poem attests, the romance was strong with this one. May I keep reading, writing, and sharing poetry for as long as he did.

The article about teens that surfaced in my news stream was from The Atlantic: Teens Are Forgoing a Classic Rite of Passage. What have you noticed about skin hunger, romance, platonic touch, or loneliness in people you know—from any generation, or in yourself? Consider sharing a comment below.

This is a wonderful article.I remember the first time a boy[Dickie] asked me in 4th grade if I would like to ride our bikes together to school. It was like touching: 1st time I held hands walking around a lake was electrical.I am not in a romantic relationship, nor do I care to be, so I am getting a massage tomorrow after a long hiatus. Hurray for touch.PS I hug my friends more too. The response is soothing during these hard times.