Silence and Inspiration in Alabama

Reflecting on three women, two monuments, and my not-really-retirement plan

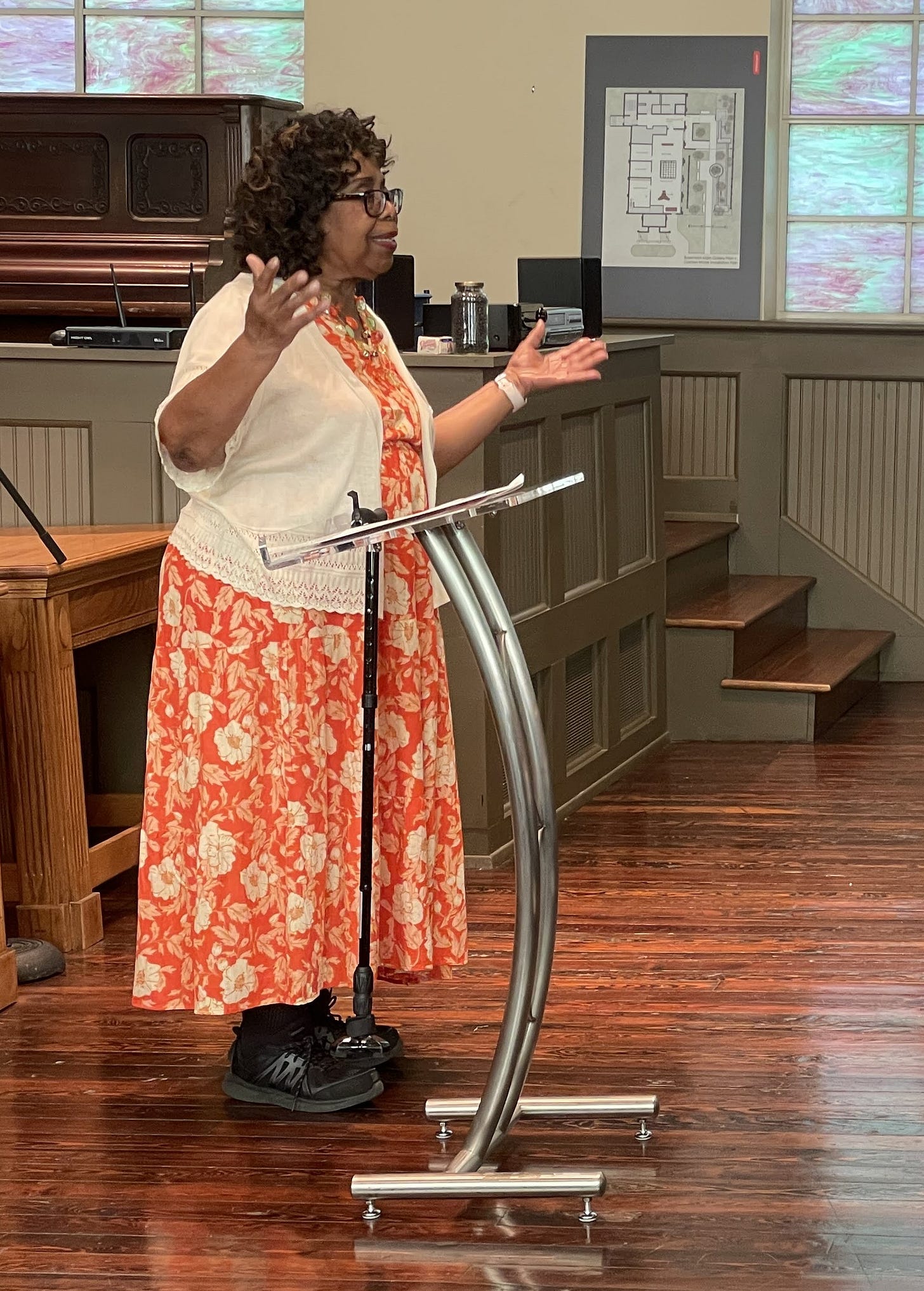

“You!” the woman in an orange print dress commanded with a smile, pointing to a goateed man wearing a black leather jacket and baseball cap. She gestured for him to come forward, pressing a section of rope into his hands before declaring, “You’re Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth.”

She turned back to the crowd.

“And you!” she beckoned to an older, stockier man in a gray button-down shirt. She positioned him facing the man in the leather jacket, a strand of red tape dangling from the middle of the rope stretched between them. “You’re Bull Connor.”

Thus began Dr. Martha Bouyer’s vivid illustration of the integration standoff in Birmingham, Alabama. I sat amid an audience of about 40 travelers from 15 states rapt in this gifted educator’s spell.

A former history teacher and Social Studies administrator, Dr. Bouyer is the Director of the Historic Bethel Baptist Church Foundation. This dramatization was part of a larger lesson about the struggle for civil rights in Alabama, particularly the church’s role under the ministry of the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth.

She threaded pieces of her story into the lesson too. Shortly after she’d retired from Jefferson County Schools and been elected to a four-year term on the School Board, her daughter told her she’d found just the right job for her (even though Dr. Bouyer wasn’t looking for one)—and showed her the Director posting.

Her gaze swept across the pews as she described her calling to continue educating people, especially teachers, about the Civil Rights Movement, explaining how opportunities have unfolded again and again since she became Director, such as the NEH Landmarks Workshop she developed that attracted 12 teacher cohorts: Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy.

“Some of y’all think you’re retired,” she challenged, expectation in her tone. Several folks laughed—hopefully, nervously, or maybe both.

Her eyes and stance conveyed the rest of her message, each of us hearing a slightly different translation. In my mind, it went something like this: but since you’re sitting here, the universe likely has other designs on your time.

Her message and lesson left an impression.

That moment was part of a journey I experienced last week on an interfaith Living Legacy Pilgrimage (or LLP) to sites in Alabama connected to the struggle for freedom and equality in America, with a focus on the fight for African Americans’ right to vote.

Parts of that struggle took place at sites we visited, such as Bethel Baptist in Birmingham, Dexter Parsonage Museum in Montgomery, and the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. We also stopped at sites created to preserve, honor, and raise awareness of this history, including the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and Lowndes Interpretive Center.

A key element of Living Legacy Pilgrimages is the opportunity to hear from veterans of the Civil Rights Movement like the founder of Foot Soldiers Park, Ms. JoAnne Bland, who I first met on an LLP thirteen years ago.

By the time she turned 11 years old, JoAnne had been arrested 13 times in the fight for civil rights. Why would a child do this? Ice cream. Here’s how she explains it. One day as she pleaded with her grandma to let her go into Carter Drug Store and eat ice cream like the white kids inside were doing, her grandma told her that when she got her freedom, she could sit at that counter too. Until then, it was against the law. In that moment, JoAnne understood the “good freedom” for which her grandma and Selma activists like Amelia Boynton were fighting. She joined them that day.

She can still hear the sickening thud of a woman’s head hitting the pavement near the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday and feel the terror that coursed through her body as police on horseback pursued protesters from the bridge back to their neighborhoods and up the stairs of First Baptist Church. Yet she continues to fight. Now on the other side of 70, the fire ignited in her at eight still blazes. Retire? Not this foot soldier.

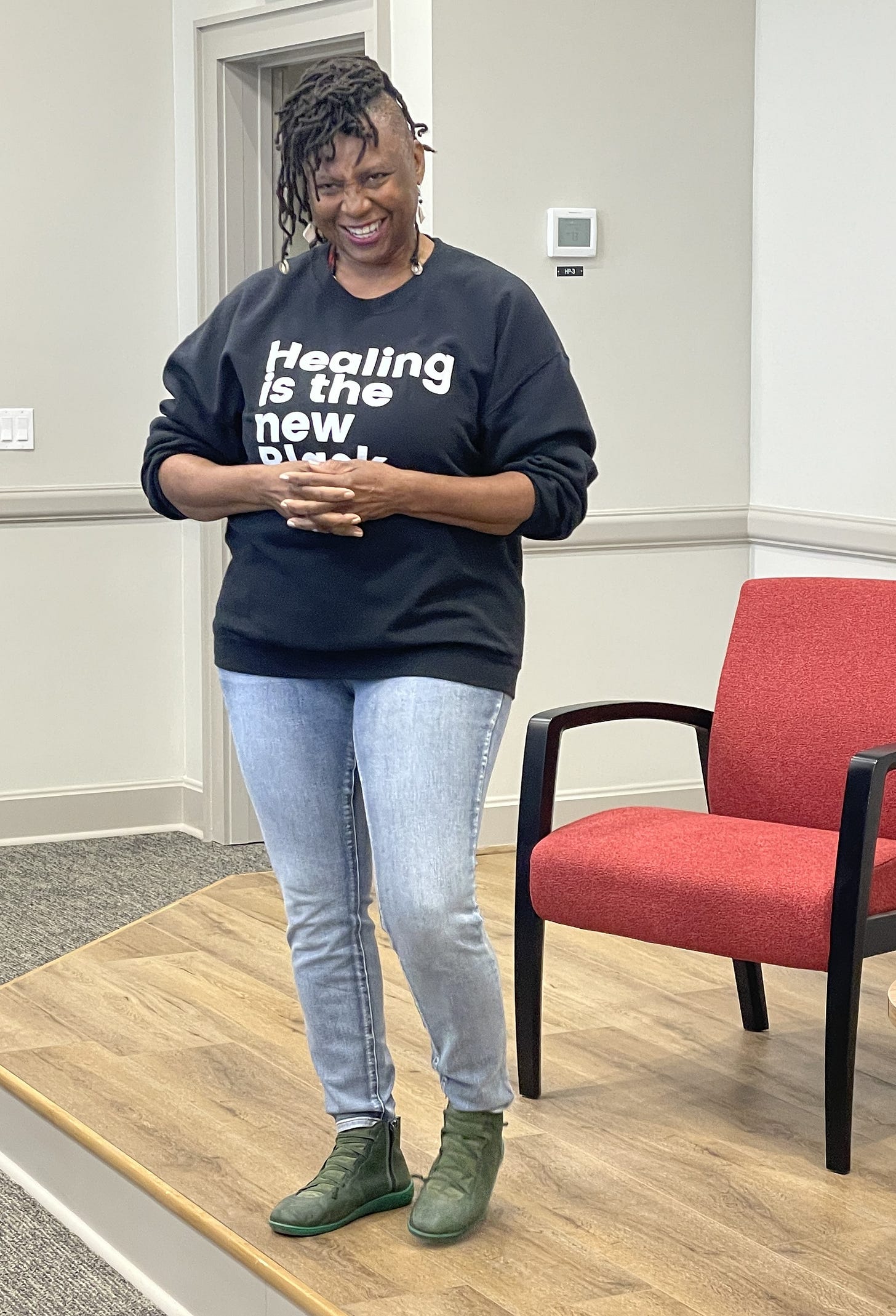

After we assembled in her new teaching space in a restored building near the infamous bridge, Ms. Bland’s talk was familiar—until she introduced a surprise guest: Ms. Afriye We-kandodis, co-founder of By the River Center for Humanity. She strode into the room emanating joy and positivity, her sweatshirt proclaiming in tall bold letters Healing is the new Black.

With a beaming smile and booming voice, she invited us to follow her lead. Echoing both her words and gestures, we hugged ourselves while shouting “I love me!,” stretched out our hands while saying “I love the color of my skin” (a skin color I was keenly aware of in that moment), and reached forward and back while declaring, “It is my responsibility to reach out in the spirit of love, to reach back with compassion, and to choose to see the beauty of God in all people.”

Then, as the irresistible rhythms of Jon Batiste’s “Freedom” filled the room, we danced, collective joy expanding with each exuberant verse. Ms. We-kandodis concluded by urging us to ask ourselves, “What will I do with my freedom today?”

I doubt there was much focus on self-care during the years when Jim Crow laws and the people who supported and enforced them oppressed Black Americans, at least not self-care as we know it. Most people fighting for civil rights relied on faith and songs for the balm they needed to keep marching.

Even though the pilgrimage I was part of in 2011 was twice as long as this one and traversed both Mississippi and Alabama, I don’t recall any Movement veteran, docent, or speaker promoting mental health and self-care the way Afriye does.

This addition bolsters my hope for the future.

Nowadays, many people answer “none” to questions about their faith community. Yet “nones” need a balm for their pain too, including the pain of confronting difficult history or navigating generational trauma. Raising awareness about mental health with practices like these could help leaders and foot soldiers of today’s social justice movements maintain their wellbeing and stay in the fight.

They might also bring healing and hope to a student—or anyone—who feels isolated or finds it hard to love themselves.

Her affirmation exercise reminded me that my own not-really-retirement plan needs to include time for what restores me. I reconnected with one such balm on last week’s pilgrimage: silence.

At the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, signs remind visitors that this is a sacred space, a sacred space to explore quietly and respectfully. On the long walk up the hill and down into and through the memorial, footsteps and breaths mixed with wind and birdsong as I walked slowly beside and then gradually below hundreds of rectangular steel boxes hanging like bodies, each stamped with a state and county and the names of people killed there by racial terrorism between 1877 and 1950.

The quiet expanded my awareness, amplifying the gravity of this era’s violence and the terror it sparked, the senselessness of the killings, the tragic loss of the more than 4000 people memorialized, and the courage and endurance of their spouses, children, descendants, relatives, neighbors, and friends who kept living and moving forward despite their grief and fear.

It also made space for imagined scenes as I read signs such as this: Elizabeth Lawrence was lynched in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1933 for reprimanding white children who threw rocks at her.

The power of silence found me again at the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery designed by Maya Lin (who also designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in DC).

Here, our group walked slowly around the circular water table at the memorial’s center without speaking, fingertips submerged in water that flowed almost imperceptibly toward us and over the table’s edge as we touched each event engraved in the black granite, each name of a fallen Movement leader or foot soldier.

Images from the past surfaced in this silence too, often from remembered photos or news footage. In this smaller space, with all of us moving together rather than on separate paths, emotions pooled and swirled—sorrow, anger, gratitude, resolve. Once everyone had completed their walk, we joined hands to generate and receive a balm common during the Movement: song (another hallmark of Living Legacy Pilgrimages).

Martha Bouyer. JoAnne Bland. Afriye We-kandodis.

May I strive to have the kind of meaningful, community-enhancing, love-centered non-retirement that these remarkable women are living—and may the fire of their commitment stay ablaze for many years to come.

And silence.

May I respect its role in restoring introverted, contemplative me. Beyond the four (sometimes eight) minutes I currently set aside for meditation most mornings, may I clear the table of my mind regularly in my next chapter. May I make space for wide, long, deep silences—silences in which a call from the universe about what to do with my freedom, if such a call is coming, might emerge.

May it be so.

Here are two poems for your pocket this week: “Invocation” by Elizabeth Alexander, a poem engraved on a tall granite slab near the end of the pathway that winds through the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and “What Remains,” a poem I wrote on the 2011 LLP. My poetry writing was in its early stages then but I appreciate the way reading the poem transports me to that stop in Money, Mississippi at the remains of Bryant’s Market, the store where fourteen-year old Emmett Till’s alleged remark to the white woman behind the counter led to his brutal murder days later. I also remain deeply grateful to About Place Journal for including it in their special issue, 1963-2013: A Civil Rights Retrospective. This was my first published poem after I started to work on becoming a better poet.

I love everything about this post, you spoke so movingly of what you experienced, Wendy, thank you. And yes, silence as a way to experience the world from a quieter, deeper perspective. (The photo of the hanging “coffins” featured Christian County, KY, which is where I was last week, visiting the area my grandfather’s family was from. Four lynchings there, three during the time my ancestors lived there, and it makes me wonder, and also appreciate how far my family, and I, have come, hopefully, since then, but how much farther I have to go.)

Thank you Annette for being the warrior that you are. You inspire me. Roxanne