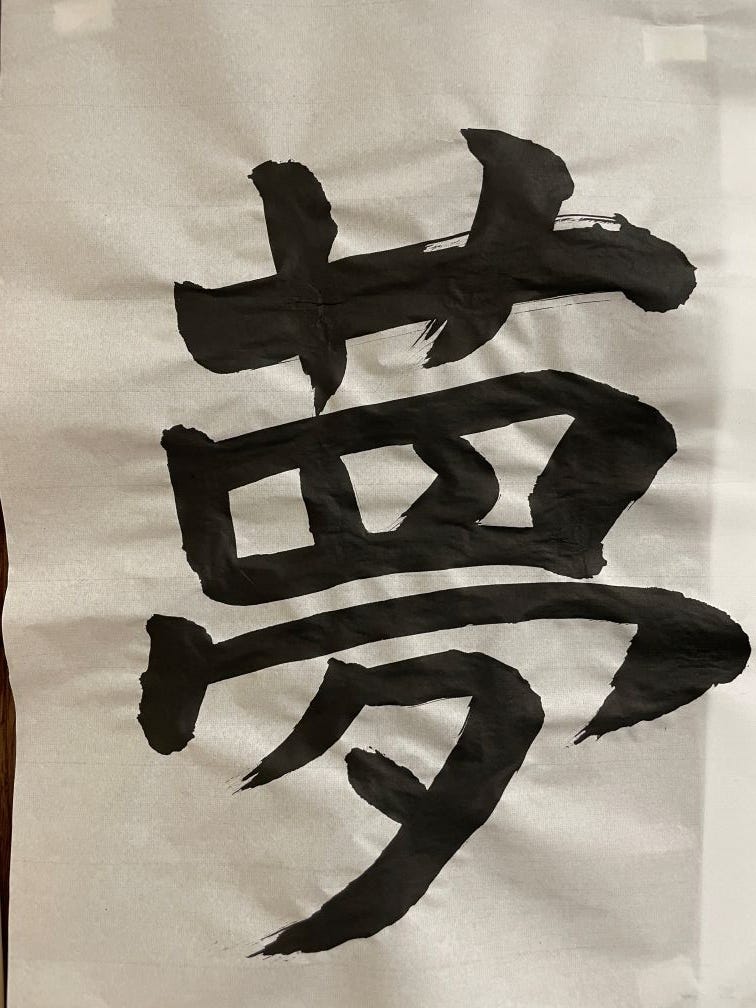

Grief, an Unexpected Doorway to Dreams

Reflecting on the recent death of a friend and my subconscious mind's response

I’m not a dreamer. I mean, I am a dreams-for-the-future dreamer, but my sleep is seldom marked by dreams, at least not ones I’m aware of. My wife, on the other hand, frequently dreams and remembers them, sometimes regaling me with their circuitous mash-up plots. A friend’s recent death disrupted this pattern.

Grief is known to shake up sleep and dreams. Dreams that feature the deceased, whether in remembered scenes or new experiences or conversations, are called grief or bereavement dreams (LA Times). Theories vary about what purpose, if any, they serve. One 2019 Canadian study suggests that such “dreams […] help us survive personal tragedy. Grief dreams may help regulate the emotions of the bereaved, who often have a hard time sleeping (in large part because our bodies secrete more of the stress hormone cortisol when we’re grieving).”

But my dreams don’t include my departed friend. Instead, storms and power outages that plagued our region this winter take down trees and power lines in my dreamscape too. Disparate details from television shows, books, and news articles melt into the brew, dreams rising through the dark with a hodgepodge of settings, characters, and plots. What do they share? Themes of loss, betrayal, destruction, violence, and fear.

I wake in the wee hours, heart racing, eyelids squeezed shut, holding my breath—or with a sense of grasping for something just beyond my sight. When I try to recall what happened, details elude me, though sometimes an image or scene, often an unsettling one, sticks. The emotions linger, making me reluctant to close my eyes. It’s as if my friend’s death shouldered open a door that’s usually latched closed.

Death also has a way of reshaping my dreams for the future. If not the dreams themselves, then their timeline. I’ve experienced this before. Three years ago, when a closer friend died suddenly, she was a few months from retirement with her and her wife’s plans for that chapter beginning to coalesce.

This friend was close to retirement too, though not as close. The last time we discussed it, his plan was to “graduate” with the Class of 2028. He mused aloud about living year-round in a small river town, downsizing to a modest house with a kickass kitchen and deck, relaxing with his family and dog and on his boat, and becoming a granddad (his first grandkid was on the way).

On his four-year rollercoaster with cancer, he continued to work, choosing to stay on the retirement timeline he’d envisioned before the cancer materialized. It was part of what kept him strong, he said—seeing students each day, engaging in this work he’d chosen, making a difference. He worried that if he stopped, he’d dwell on his illness to an unhealthy degree.

Yet, he took care to play more too—spending more time at home and at the river with his wife, family, friends, and dog; tailgating at Virginia Tech, listening to jazz in New Orleans, taking a magical winter trip to Iceland, chaperoning a school trip to England on spring break before a round of treatment started, and savoring wine, beer, and favorite foods in good company.

His “sage advice” read at his memorial service reflected these priorities: Go & do everything, even when you’re intimidated and afraid; eat pizza and chili Fritos; sit by the water as much as you can; spend time with your family; travel anywhere & everywhere you can; listen to music, especially live music; eat good food; be kind, be fair, and be tolerant because it makes the world a better place; use the china; burn the candles; drink the good wine. Live the Fritos out of life. Tomorrow is never promised. He lived this advice. And his faith, including his belief in an afterlife, gave him comfort and peace.

In the aftermath of my close friend’s sudden death three years ago, I re-evaluated my plans for the future. Instead of waiting until I’m 65, I decided to retire from full-time librarianship as soon as it’s feasible. I started this Substack last year to help me figure out what to do next. In the wake of this friend’s death, I plan to live each remaining year as a librarian like he did his last four—with an intentional commitment to joyful play, personal growth, and giving back.

Some of my joys share a kinship with his. I love the river yet prefer to navigate it in a kayak rather than a power boat. I savor pizza but like my Fritos plain. My soundtrack? More folk than jazz. Then there are the joys that don’t overlap with his, like writing. Although writing wasn’t his thing, I expect he’d raise a glass to the fact that I’ve written most of this post while drinking the good wine (which for me is a $16 bottle of red instead of an $8 one).

Words blur on the screen as I type. I miss them both. In keeping with the “sage advice” above, I’ve been focusing on the present. I walked beside the river with my wife on Tuesday, searching for bluebells that have just begun to break the soil’s surface. Yesterday, we indulged in delicious slices of Guinness gingerbread in the spirit of St. Patty’s Day. At school, I talked to a colleague about the possibility of organizing an international school trip for 2027, something neither of us has done before and that scares me a little but would stretch me in new ways.

My nighttime dreams have shifted. While I’m still actively dreaming and those dreams still resonate with loss, I no longer wake with my heart racing. The initial storm surge of grief that swept through my mind is ebbing. I don’t understand what has changed but I’m fine not knowing. Our bodies, our minds, hold mysteries that even humans generations from now may not understand.

I taught a lesson today about the roots of secular mindfulness and yoga in America. As I revised my slides, I ran across a quote from a local counselor and coach who influenced how I teach mindfulness. Less than two years after I observed him teaching his students, he was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer. Applying mindfulness, which he’d first learned about at 15, he and his family adopted a motto: Make plans but have no expectations. On Monday, it will be eight years since he was told he might not make it through the weekend.

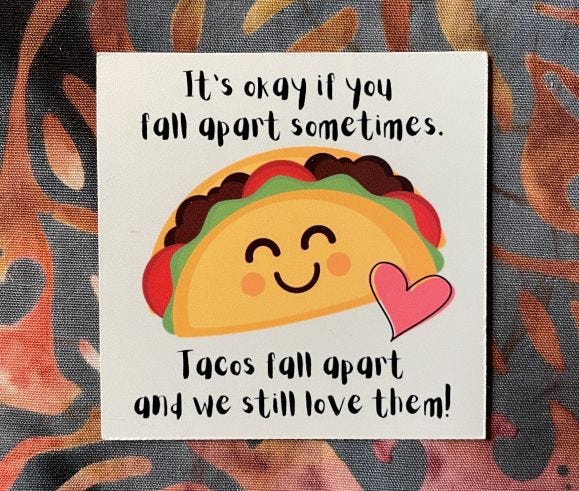

In a trailer for a documentary about his journey, he says that applying mindfulness to pain, mental or physical, is not intuitive because it teaches you to turn directly toward the pain, tuning into it so that you can move through it or accept it and adjust. The counselor I spoke with last month had a sticker on her laptop that read: It’s okay if you fall apart sometimes. Tacos fall apart and we still love them! Letting intense feelings flow through you is one way of being present to the moment, to your pain, and to yourself.

I feel love and joy freely but resist turning toward sorrow, anger, or shame. My impulse is to distract myself from emotions that might make me lose control, particularly in front of students (despite the taco’s assurance that it’s OK to do otherwise). As I learn to face such feelings mindfully, I prefer to do so at home. Maybe, in the meantime, my dreams can be a place where those encounters take place, even if I’m not fully conscious of them.

Here’s a poem for your pocket until the next post. I wrote this on the second day after my friend’s death. It may not be finished yet but here’s the current draft: After a friend dies and the box where I’d stuffed my grief, cried open, won’t reclose (PDF).

What is your experience with grief and dreams? Share a comment below. If you like the taco sticker and want to order some for yourself, you can find them on Etsy.

Thank you, Wendy. Being present in the moment - unapologetically present - invites others to do the same. I'm used to running a "tight ship." But now it's a "leaky vessel" as I find myself more often in tears.

Well said with compassion and humor. Thank you for sharing and inviting me to ponder losses but also their lifelong gifts to me and others in their circle.