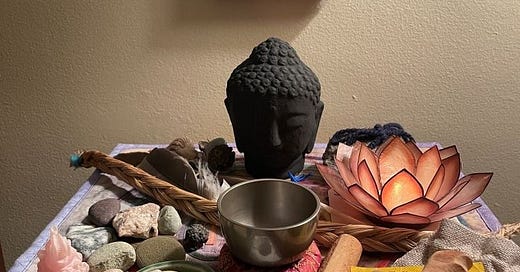

I hold the Buddha head in my hands, wiping dust from the sculpture’s surface and crevices with a damp cloth. As I turn the figure on its side, I find myself cleaning the tiny bowls of its ears, feeling the weight of the head in my palm, recalling the friend who gifted it to me, now gone.

It’s fitting that this quiet act was part of a deep cleaning inspired by poet Jane Hirshfield who was once a Zen monk. Facets of her New Year’s ritual, a Japanese tradition called ohsoji, have surfaced in her poems over the years. In keeping with this tradition, Hirshfield cleans every surface in her home during late December: each ceiling corner and windowsill, each track light, each tile and wood plank, clearing off every shelf, picking up every pile from the floor to wipe underneath.

This “big cleaning” in preparation for New Year’s symbolizes the “sweep[ing] away of a year’s worth of ill fortune and evil spirits in anticipation of a fresh start” (Hiroko Yoda, The New Yorker, 2021). Spreading from temples and shrines to many households by the seventeenth century, the practice was first known as susu-harai or the sweeping of the soot. Although the tradition has dwindled in Japan over recent decades, Hirshfield continues to find the practice renewing.

Cleaning is not at the top of my list. I strive to keep things tidy enough that I know where things are (not always successfully), but if a woodland walk, emerging poem, bird, book, or friend beckons, you’re unlikely to find me with dustcloth in hand (dusting perhaps the most neglected chore). My first chapbook included a poem called “Why the House Isn’t Clean.”

Despite this pattern, a gap in the invisible force field between me and more than cursory cleaning opened briefly this month. I’d just heard Jane Hirshfield read poems and talk about Poets for Science at an online Hellbender Gathering of Poets. She mentioned her New Year’s ritual, smiling when she noticed the stacks of books visible on the table behind her. I moved them there, she said, so I could clean the bedroom floor. Faces across the patchwork of Zoom squares smiled back.

Just as I do on most school breaks, I embarked on winter break with an aspirational list of tasks, including decluttering my study. On the eve of that last Sunday, I had yet to sort a single pile. Then, it snowed—and kept snowing, more than we’ve seen in years, enough to close school for three days. Snow days. There’s always been something magical about them.

Lit with snow-day magic, I waded into the papers, magazines, books, and overflowing boxes on and under my desk, in front of bookcases, beneath the windows, and beside the dresser. The paths to the chair and closet, and the patch of rug where I unroll my exercise mat were the widest open spaces on the floor. Unsure where to begin, I worked clockwise, starting with the dresser top.

Emotions bubbled up as I moved from pocket to pocket.

There, tucked under a calculator, a funny rhyme written by a friend for my birthday five years ago, a friend who has since lost the ability to write.

The next day, a small Buddha Board stuffed between books about drawing and death. I opened it, poured a few drops from my water bottle into its tiny trough, picked up the brush, and drew strands of grass. As I watched the brushstrokes disappear, I remembered how such drawings rehearse, again and again, letting go of attachment.

Hours later, I uncovered three blocks of wood passed on to me after the sudden death of a friend who’d intended to carve them. Then, pen refills, purple and black. Maple sugar candy—hardened but still tasty.

I encountered innocuous detritus too—receipts from the plumber and pharmacy, library and teaching magazines, and sticky notes with jottings I could no longer decipher. Before long, bags of trash and recycling bulged and stacks of papers sorted for filing fanned out around me.

Next came the towers of books. Where could they go? Luckily, we had two thin shelving units in the shed, stored there since we moved five years ago (book lovers that we are, we seldom get rid of shelves). Though designed for DVDs and CDs, I repurposed them for books. One fit beside the door. To squeeze the other onto the wall behind my desk, I removed everything from two large bookcases so I could scoot them four inches closer to my window. As I dusted the empty bookcases and the walls and baseboards behind them, I recalled Jane’s ritual and grinned.

After I finished decluttering, sorting, dusting, and reorganizing, I vacuumed and ran an air cleaner. I don’t know how long the process took, suspended as I was in snow-day time. Power outages limited me to daylight hours for some stretches and pulled me away to set up the camp stove and propane heater. Burst pipes at a water treatment plant triggered a boil advisory for people across the city, spurring friends to stop by to take showers or fill water jugs. Days passed fast and slow.

What I do know is how I felt afterward—like a stone tumbled to shimmering. Maybe it was the cascade of emotions that flowed through me as I worked that buffeted me, knocking some stuck junk loose. I felt calmer too. Was it having each book shelved and each kept card or paper filed, or was it just knowing what was where? The room even feels more spacious, as if some stubborn tension has drained from it, as if there’s more air, molecules expanding into once jumbled spaces.

While I cleaned, I noticed my attachment to things—stones picked up on hikes, pinecones and shells, love notes from Annette, travel souvenirs, childhood trinkets, journals, favorite books. Looking at them, holding them, rereading them brings me comfort. No matter how many water drawings evaporate from my Buddha Board, I expect my attachment to these objects will endure for as long as I continue to recognize them, for as long as the universe and chance allow me to keep them.

While I cleaned, terrifying wildfires blazed across neighborhoods near Los Angeles. We were tracking this news during the snow days too. Friends we’d visited in Pacific Palisades last summer lost the home they’d lived in for decades. At first Annette couldn’t reach them, then she got a text. The family had evacuated to safety, including their cats, but fire had destroyed their home, school, library, grocery store, and more. In later texts and calls, she learned that they’d secured a place to stay for the rest of January and were scrambling to get the kids back in school. Heartbreaking.

I tried to imagine how unmooring it would be to lose so much. I couldn’t. I tried to imagine how it would feel to lose everything I’d touched over the last few days in an instant. I couldn’t. I doubt there’s a way to prepare yourself mentally or emotionally for the kind of devastation that people displaced by the L.A. wildfires or the catastrophic floods from Hurricane Helene have experienced, only the hope that if you make it out alive, you can navigate the aftermath.

Attachment can intensify the pain from such tragedies. Does that mean I will learn to surrender attachment? Unlikely. I strive to cultivate non-attachment through meditation and reflection, not to grasp things, places, people, or outcomes too tightly, but I also want to be rooted. I recognize the contradiction and choose to embrace rather than untangle it. People matter to me. Place matters. And so do some special things in our home. Less attachment might make losing beloved people or cherished places or things hurt less, but it would still hurt like hell.

Will I adopt Jane Hirshfield’s whole-house deep cleaning ritual next December? No. My one-room variation satisfied me. Will my study stay tidy? Maybe. But I suspect, over time, it will drift back into disorder. That’s OK. I didn’t expect this to be an epic turning point in my tendency toward clutter. Yet, having such a thoroughly clean study is certainly a refreshing and centering way to start the new semester, and I’m grateful for that. Thank you, Jane. Thank you, snow.

May the winds be calm around Los Angeles this week and rain fall to help extinguish the flames. May the thousands of people uprooted by the wildfires find safe places to stay and get back on their feet. May the attachments that matter most to you remain close and bring you comfort.

Happy New Year, readers. Here are two poems for your pocket until the next post, both by Jane Hirshfield: “Counting, This New Year’s Morning, What Powers Yet Remain To Me” and “I would like.”

What is your experience with attachment? cleaning? New Year’s rituals? snow days? loss from floods or fire? Take a moment to leave a comment below.

Very thought provoking, as you usually are Wendy, and nice thought/writing prompts.

Beautifully written and very thought-provoking. Yes, still need to start all the weeding out process.