Breath, the Body, and...Death Beads?

A restoration, a reclamation, and an unexpected conversation about death

On Monday, I noticed my breath when I woke. Eyes still closed, I focused on its steady tide, my body a beach. When I slowly opened them, sun glowed around the edges of the window shades, washing the walls and ceiling in the soft gray of dawn.

Unbidden, unwilled, my body pulled air in, rhythm like nets cast out and drawn in from the sea. This morning, unlike so many others this summer, the path of breath from nose tip to lungs was clear, a path swept clean. Thank you, I thought silently to the universe. One day this breath will stop but today I can breathe without effort or coughing. As the day unfolded, another kind of restoration would add to my gratitude.

When my wife Annette and I first met, hiking, biking, and kayaking were our favorite ways to spend time together on the mountains, rivers, lakes, and woodland paths that beckoned us. A few years later, complications from a series of knee surgeries she had crossed biking off the list, and not long after, as getting in and out of the boat grew more difficult, kayaking too. We adjusted, continuing to walk in forests, beside rivers, and on city sidewalks, and hike trails in the Blue Ridge Mountains and elsewhere.

Monday marked a new chapter. The day before, we admitted to each other how much we missed kayaking together: watching for birds and turtles, talking, pausing for a closer look at flowers or dragonflies, and paddling in silence. We strategized about how to leverage Annette’s arm strength to compensate for the limitations of her knees. We discussed traits of nearby put-ins and decided to pick one where getting in and out happened near the bank or shore rather than from a platform or dock. We debated about props, settling on a garden stool, step stool, cane, and hiking staff. We considered taking a hoe too but decided that without a dock, it wasn’t likely there’d be a place to wedge the blade so she could pull herself up.

When we arrived at the reservoir, we set out our options. Our plan was to practice first before her arms or mine had tired from paddling. With me steadying her boat, she got in with little effort, plopping into her seat like I do. We may not look graceful, but we get there. Then came getting out. Annette positioned the stools, cane, and staff. I steadied the boat while she lifted herself onto the kayak’s edge, transferred to the low, flat step stool, then pushed herself up using the garden stool. She’d done it!

Let’s try it again, she said, grinning and moving the cane and staff aside since they hadn’t been useful. I bent to stabilize the boat, a matching grin lifting the corners of my lips. Kayaking was back on our list.

As we paddled away from the put-in, I took a deep breath of the warm morning air, sensing my hands as they held the paddle. I watched Annette’s back, her torso rotating slightly from side to side as she paddled, head tilting up as she looked for birds. Why did we wait so long to find a way back to the waters we both love?

I don’t know. Maybe continuing to paddle solo, something I’d done before we met and experience as a blend of meditation and communion made me think of kayaking more as mine than ours and as a result, I didn’t bring it up. Maybe it was the way we tend to picture our bodies from the inside, remembering them at their most capable—when we could stretch further, crouch easily, lift more. Gradually, often without conscious deliberation, we opt for activities we can still do as we always have, or close—and let others slip away. I’ve done it with anything than involves jumping. Maybe Annette had done it with this. Is that pride? Stubborn optimism that we can restore our bodies to their former limberness? I’m not sure about that answer either.

I suspect distance and convenience were factors for us too. When we lived further from put-ins and didn’t have a pickup truck to transport two boats with ease, sticking with me paddling solo kept things simple. No need to fuss with how to get both boats to the water. Yet how much trouble would it have been? We had a roof rack we could have attached to the car. But enough second guessing why neither of us pushed for this moment sooner. We can paddle together again.

Stroke by stroke, we reclaimed this part of us. Nature returned our embrace. Belted kingfishers, two pairs, chittered and dove as we paddled past, an osprey called out as it launched from a bare treetop, a trio of cormorants, slender necks turning like synchronized swimmers, glided across the water, a white heron alighted on a leafy branch to preen and later hunted in an inlet thick with lily pads, lowering its beak to rest motionless against its body before darting to snatch a fish from the shallows, and beside a green heron camouflaged by foliage, a swamp mallow bloomed, cones of pale yellow petals open to reveal the rubies inside.

Perhaps even the summer games in Paris spurred us toward this reclamation. Our bodies, in that journey from our first breath to our last, change in ways we expect and sometimes, due to illness, injury, or other challenges, in ways we do not. When I watch Olympic athletes, I often catch myself thinking, eyes and mouth wide in amazement, are those really human bodies?, steeped in wonder that a body from the same species as me can be trained and conditioned, shaped and strengthened to move through water with so much power it leaves a wake, to flip and spin—to fly. They show us what the human body is capable of, and through new stories shared during each Olympics, we also learn what many athletes have endured, overcome, or sacrificed to reach that stage. This wonder is not a product of chance.

What will happen to the decidedly non-Olympian edition of this body, an edition I deeply appreciate, when the breath that sustains it stops?

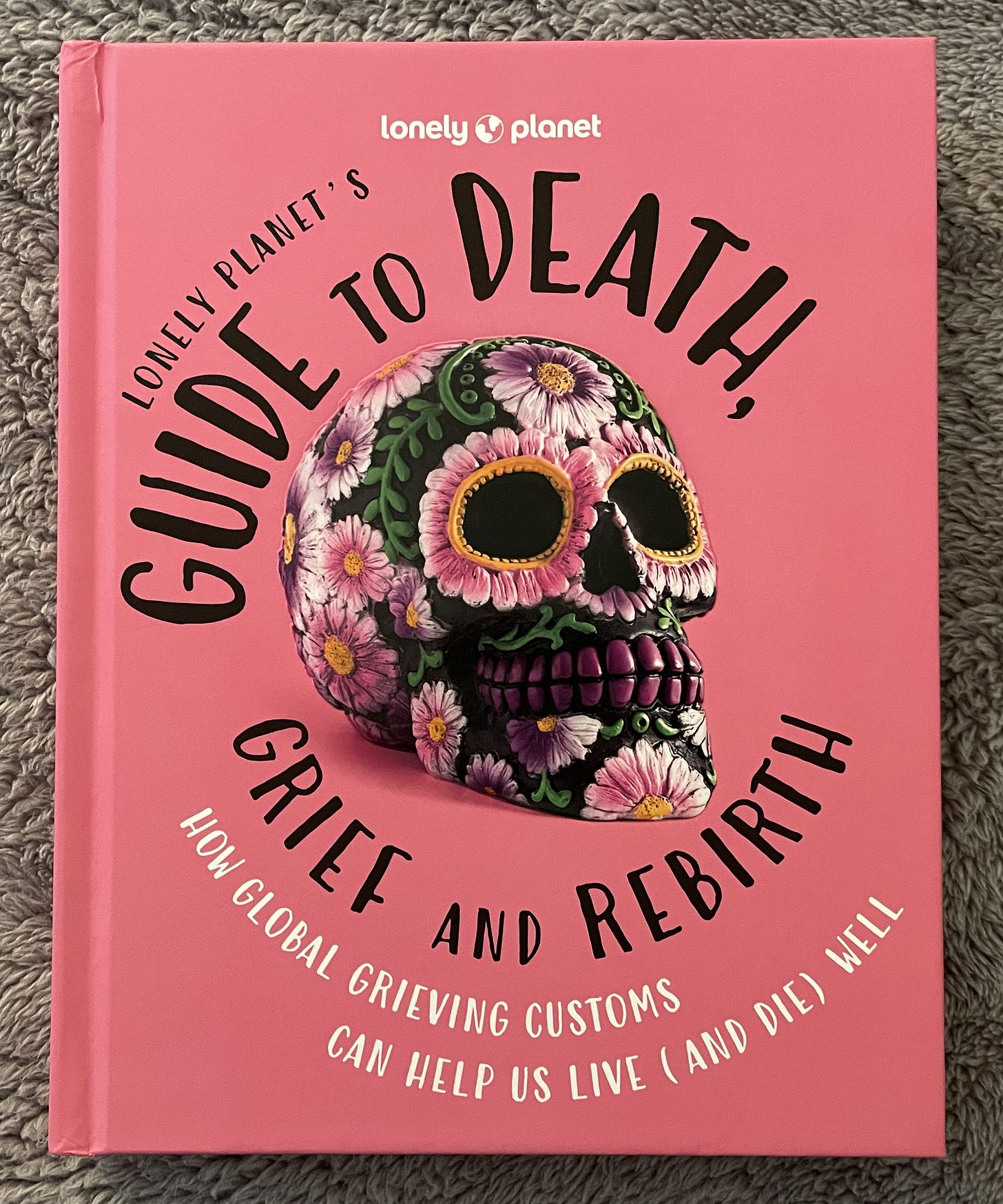

On the last day of the American Library Association conference this summer, most vendors gave their books away. The friendly folks staffing the Lonely Planet booth decided that at 12:30pm, attendees could take one book each. They had only three copies of the one I wanted, a new publication being given away the day before its official release: Lonely Planet’s Guide to Death, Grief and Rebirth: How Global Grieving Customs Can Help Us Live (And Die) Well.

Eager to read it, odd as that may seem, I grabbed a snack and queued up 45 minutes early. My determination paid off. I got a copy and finished it on our flight home. Yet when it came time for my monthly book group, a group where we read whatever books interest us and tell each other about them when we meet, I hesitated. Should I take this one? Would they think I’m weird or be upset with me for bringing up such a somber topic? One of the women had lost her husband just a few months ago. Was it insensitive to share it?

Death in fiction, in mysteries, thrillers, and such, wasn’t an issue. We discussed death in that context regularly. But this was about customs around human mortality, and in a group of mostly retired women, it would bring our own mortality front and center. Silence tends to descend when that happens. I’ve met many people, my parents included, reluctant or unwilling to discuss their wishes about what might bring them comfort in their last days, weeks, or months—if death comes with any notice, or what they’d like to happen to their body when their breath leaves it, silences that can lead to confusion, stress, or conflict among survivors who try to guess what those wishes might have been. I slipped the book into my bag—and took another just in case.

When my turn came, I held the book up, its hot pink cover practically glowing in my hand, and highlighted three chapters that lingered with me:

Swedish death cleaning – a sort of Marie Kondo style of preparation which centers on sorting through and reducing your accumulated physical possessions to “relish a joyful and clutter-free life” in your later years and spare loved ones from “an almighty clean-up” after you die (189). Margareta Magnusson, who promoted the concept, suggests beginning the process in your sixties.

Romania’s Merry Cemetery – a “kaleidoscopic” cemetery of bright blue grave markers with colorful portraits and white lettering that memorialize the dead in their wholeness, complete with warts and quirks, reflecting the possibility of finding laughter amid the sorrow that death brings (65).

Korea’s cremation beads (a.k.a., death beads) – a custom of creating beads from crystalized ashes, an option marketed in South Korea after a law passed in 2000 that requires people who bury their loved ones to exhume the body after 60 years, a regulation intended to encourage more people to opt for cremations due to the limited land in this rapidly growing nation (83-5).

Since I wish to be cremated, this last custom fascinated me. What might it mean to transform ashes into beads rather than scattering them—beads that could be gathered onto a string like a rosary, rolled between the fingers or pressed into a palm while praying or remembering, used to create jewelry, or kept in a jar or pouch. When I looked up this custom to verify that such a law existed, I discovered that the ashes from an adult body typically result in four or five cups of beads. That’s a lot of beads.

This reminded me of something a friend told me when I read an early draft of my poem “If I Die First” to her. Referencing a line in which I suggest putting my ashes in a mason jar, she asked, “Have you ever seen cremains?” Then, without waiting for a reply, added “You’d need a very big Mason jar” (an exchange I mentioned in an earlier post related to ashes). I smiled as I recalled the conversation, tightness gripping my throat and chest as I wished I could tell her about this custom and lend her the book, but she took her last breath in 2022.

As I wrapped up my remarks, one of the women reached out her hand. The next thing I knew, the book was being passed around the tables we’d pushed together at the back of the grocery store café. As it moved from hand to hand, stories about death emerged, and wishes, and questions. I shared what my friend had said about the mason jar.

Seated in my favorite coffee shop, an empty travel mug beside me, I study my hand as I write these words. I tune in to my breath, notes of coffee and toasted bagels in the air. As my body changes, I vow to do my best to adjust, to keep mountains, rivers, and forests in my life for as long as I can. And when I can no longer figure out how to get to them and don’t want to let them go, I’ll take a deep breath and reach out to someone I trust to help me find a way forward.

Here’s a poem for your pocket until the next post: “Burial” by Ross Gay, one of the sparks that inspired me to write “If I Die First.” If you’d like to hear him read it, watch this video from his 2015 reading as a Finalist for the National Book Award (he starts reading “Burial” at about the 1:27 mark).

It is so easy to see the peacefulness and love you both find in kayaking. Plus your love of nature.

Thanks for sharing life and breath thoughts. Of course it brings tears to my eyes like you poem “If I Die First”.

Love the idea of beads. It would make the deceased feel they are still with you and enjoying a part of life and hoping they bring peacefulness to help you through hard times.

Wendy, it was lovely to start my day with you! It allowed me moments to be present with you in the kitchen, sharing thoughts as you mixed the blueberries & protein powder as we shared the early morning time together. I loved this piece and its fullness of life and breath! Thanks too for the poem Burial…what a marvelous image of the interplay between tree & ashes, between life and life after death. Happy Friday dear one. Thanks for your multiple gifts and blessings!