Why AI Makes Me Want to Keep Teaching

Questions, fascination, and fears about generative AI in education and beyond

I kept a wand and a tall wizard hat—purple with silver stars—in my library office when I experienced my last big education shake-up: the rollout of the iBook Teaching and Learning Initiative in Henrico County Public Schools (HCPS). In 2001, it was the largest 1:1 computer initiative in the country.

Titles from the Harry Potter series topped the banned book list, the Human Genome Project released the first maps of the human genome, and high school teachers in HCPS received their Apple iBooks in time for pre-summer professional development. Some faculty decided now was a good time to retire.

More than half of HCPS students lacked access to a computer at home, and many school and county leaders, community members, teachers, and parents hoped the program would bridge the “digital divide” between them and students who did. Those who opposed the initiative raised concerns about its cost, its potential negative impacts on teaching and learning, and what students might encounter online.

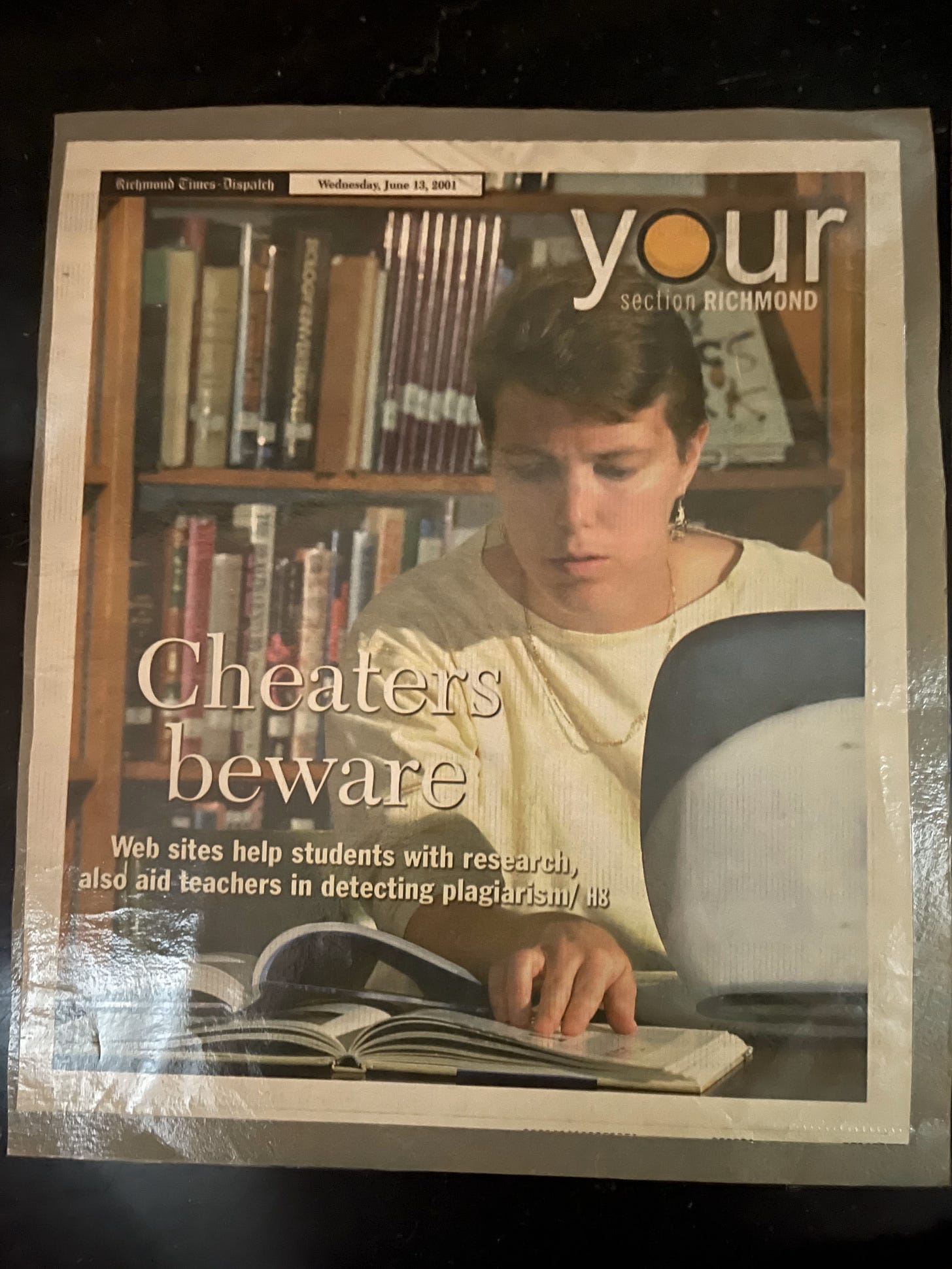

Teachers on both sides worried that expanding access to the Internet would result in more cheating. Just before summer break, the local paper ran a cover story about the topic in the Your section: “Cheaters beware: Web sites help students with research, also aid teachers in detecting plagiarism.” That’s me and my new iBook in the photo.

Some people questioned whether high schools would still need libraries or librarians once students could access the Internet from anywhere on campus. I knew they did, perhaps more than ever. So, when the library supervisor who’d mentored me announced her retirement, I applied. No colleagues I’d asked were interested in the position, so this was my attempt to ensure there’d be a pro-library advocate at the table if someone floated a proposal to cut libraries or librarians. I started the job on July 1, about eight weeks before thousands of students received iBooks.

This generation’s latest education game-changer, generative AI, is shaking things up again. OpenAI released ChatGPT in November 2022. Instead of costing millions like Henrico’s 1:1 initiative, students and teachers could access this innovation for free like they could Google, Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok. It attracted a million users in less than a week. The media quickly portended a meteoric rise in cheating and the end of the essay. Several schools scrambled to block ChatGPT and ban its use. For some educators, retirement looked increasingly attractive.

This felt familiar. But instead of prompting me to run a benefit estimate on the Virginia Retirement System’s web site, the emergence of generative AI and the challenges and opportunities it presents for libraries, schools, and society makes me want to stay put, at least for a few more years.

ChatGPT now has over 180 million users (Seo.AI) and that was before this week’s release of GPT-4o, known as Omni or “O” (the letter), which has some jaw-dropping capabilities. Check out this video of Salam Khan, founder of Khan Academy (known for its educational videos) testing GPT-4o’s ability to coach his son Imran through a math problem. An amazed colleague sent me a link to the video, remarking half-seriously, half-jokingly, Well…guess we’ve been replaced.

We haven’t. Teachers and librarians remain instrumental to students’ growth, learning, and wellbeing—even in the age of generative AI.

There’s much more to what we do than convey content or skills. Teaching is relational. Along with the content and skills students learn through the lessons we design, teaching is about making students feel valued and seen, expanding their ability to imagine, reason, test hypotheses, problem-solve, and recognize assumptions and biases (including in their own thinking). It’s about strengthening their ability to persist when they struggle to grasp a concept and supporting them as they explore who they are and how they want to engage with the world.

That said, I wonder whether educators could leverage generative AI selectively to take teaching and learning to new levels or in different directions. Is it possible to integrate generative AI into designated assignments while also providing AI-free opportunities for students to develop their own thinking, writing, creativity, and an understanding of core concepts? I don’t know. Whatever answers emerge, librarians will likely have an essential role.

I haven’t experimented with generative AI as much as some of my colleagues or many of our students, but what I’ve learned so far fascinates and frightens me. Here’s an example of why:

In an April post in his One Useful Thing newsletter, Wharton professor Ethan Mollick cited a study that tested the persuasive capability of Open AI’s GPT-4. The setting was an online multiple-round debate which randomly paired 820 participants with either another human or GPT-4. Participants didn’t know which they were interacting with. In some debates, also randomly, GPT-4 and/or the human had access to personal details about the participant. The results? When it could personalize the debate, GPT-4 was 81.7% more likely to increase the participant’s level of agreement with its position than a human opponent.

Wow, right? And yikes! How is this possible? Why was GPT-4 significantly more persuasive than the human? What can we learn from this study? Many companies will probably harness this capability to persuade us to buy things we don’t (yet) think we want. But in what contexts could such power be more dangerous?

Concerned about the potential of generative AI to sway elections, student organizers for our library’s One Small Step program (which pairs classmates with different policy opinions for conversations about the values and experiences that inform their opinions) used ChatGPT to generate short persuasive articles on different sides of policy issues they knew well. It was a lively discussion. But we didn’t consider that generative AI might actually do the persuading.

Even the machine learning experts who develop tools like ChatGPT don’t fully understand how they’re able to do what they do. It might be math that’s powering them (more on that in a minute), but it feels like magic. When I get a new tool, I read the manual. But there isn’t one—and the technology is evolving at warp speed. This uncertainty unsettles me.

When it comes to policy issues like the ones discussed in One Small Step, there are times that I curl up in the comfort of an echo chamber of friends and pundits who agree with me. This is the last place I want to find myself when it comes to generative AI. The stakes are too high.

As I grapple with this uncertainty, I want to explore my fascination and face my fears as part of a vibrant, multigenerational, intellectual community like the one at my high school where students and faculty hold a wide range of opinions and insights about what place, if any, generative AI has in education.

Doing nothing is not an option. Just as people harmed and helped by generative AI can’t stay silent while public policy and regulation decisions are made about it, educators can’t ignore it. At the very least, schools need to ensure that students understand the basics about how generative AI works—which will keep changing. Maybe this will be a new role for librarians.

Here’s the kind of misconceptions we could help dispel:

Some people think that when they submit a prompt to ChatGPT it draws from a vast repository of stored documents, collaging chunks of text to create its response—like a supercharged search engine copying and pasting from its top search results. But it doesn’t.

As Mollick’s book Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI helped me understand, what the large language models (LLMs) that power these tools store are “weights” based on the “patterns, structures, and context” the model learns from seeing billions of documents. These weights are “complex mathematical transformations” that help predict, based on the pattern, structure, and context of the words in a user’s prompt, what a likely response would be.

An example Open AI uses in their explanation is “instead of turning left, she turned ___” (OpenAI). The likely prediction: “turned right.” This allegiance to the likely can make the responses ChatGPT creates seem eerily human and often, at least without further coaching from the user, quite bland and well, predictable. The fact that it’s predicting and not pasting also makes it difficult to trace a segment of ChatGPT’s response back to a specific line in a source text.

It also means its predictions can be wrong. Think about someone you know who, when you say or do a certain thing, you can predict how they’ll respond—most of the time. My wife, for instance, would tell you that if she shares a surprising stat or finding with me, I’ll ask for the source. She’d be right—mostly. But if I’ve already read about it, I won’t ask. Or, if she starts by saying, “I’d have to track down the article again to verify the source, but…” Well, I wouldn’t ask then either. In that case, she’d predict that her preface would make me smile. She’d be right about that too.

There’s another reason tools like ChatGPT generate inaccuracies or fabricate court cases and scientific formulas that don’t exist. When developers feed those billions of documents into LLMs to expose them to the patterns, structures, and contexts of human language, there’s no differentiation between fictional or factual texts. And if there are biases in the training documents, which there are, those can influence its output too.

Mollick puts it this way:

“Remember that LLMs work by predicting the most likely words to follow the prompt you gave based on statistical patterns in its training data. It doesn’t care if the words [it generates] are true, meaningful, or original. It just wants to produce a coherent and plausible text that makes you happy.”

Students need to understand this. Consider how misled they could be if they think ChatGPT is a supercharged search engine creating an answer from its top search results. They might accept any response that sounds good. They might not fact-check. They might submit the response to a teacher as if it’s their own, risking harm to their reputation and grade—and undermining their learning.

At the moment, ChatGPT is usually terrible at handling prompts about current events or obscure topics. Such responses tend to be riddled with inaccuracies and fabrications. Shouldn’t students understand this too? What if, without knowing this limitation, they use ChatGPT to research a rare health issue that a family member is facing? Even though generative AI’s limitations will change as the tools evolve, details like these can be taught, particularly by librarians.

What about cheating in the age of generative AI? There’s no magic wand.

The web sites that 2001 cover story alluded to—they didn’t always uncover the source of a plagiarized assignment. Similarly, our students and faculty who’ve tested purported “AI detectors” have found them as likely to label original work as AI-generated as they are to correctly identify AI-generated writing.

What allows a teacher to detect that something is off in a student’s writing is the same thing that always has: familiarity with a student’s voice and the sense that the writing submitted doesn’t align with that voice. If a student cheats and a teacher asks if they plagiarized or asks them to explain how they arrived at the answer, they’re more likely to admit their bad judgment when that teacher is someone they respect and whose trust they want to maintain. Teaching is relational.

In some cases, teachers can design assignments that deter or prevent cheating. This has been true for decades. In the context of generative AI, just as students who understand how it works are less likely to be duped by an inaccurate or fabricated response, teachers who understand its limitations can develop assignments for which ChatGPT is less useful, or even detrimental. The assessment environment matters too, with more teachers choosing to have students complete their writing or other work in class, sometimes by hand.

But where do we draw the line between originality and cheating in the age of generative AI? Students have long used Grammarly, spellcheck, and Word’s editing tools, and teachers accept these works as original even when students have this after-draft editing assistance. What if the assistance occurs at the other end of the writing process? If students create first drafts with ChatGPT, what amount of editing would make the final drafts original—or original enough?

What if they use the ChatGPT feature that allows them to upload their own writing and train a custom GPT to write like them? Is that output original since they trained the model with their own writing? What if they also write the code for the LLM? These questions deserve robust discussion among teachers and students. I want a seat at that table.

Generative AI has already changed the world we’re in and the one we’re preparing students for. Professionals in myriad fields, including scientists involved in the Human Genome Project, integrate generative AI into their workflows. Some of our students in mentorships use generative AI alongside their mentors in their labs or offices. At school, some teachers permit students to use generative AI for aspects of projects not connected to the core skills the project is designed to develop. Many students also use generative AI for tasks unrelated to school assignments, like trip planning or creating promotional materials for club events.

Recently, I’ve been using Otter.AI to automatically create transcripts and summaries of conversations. It’s a remarkable, time-saving tool. I need to experiment further with generative AI tools to see if there are other ways they can facilitate my work without interfering with my creativity.

There’s also much more I need to learn about the bigger picture. Take, for instance, the impact of mining the lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements in microchips and batteries. Or the massive amounts of water and power necessary to cool and run huge server farms that crunch the data that makes all this data-dependent tech possible. Then there’s the toll on low-paid workers employed for tasks like content labeling to improve the responses of generative AI, or to screen and edit how the chat assistant on a company’s web site responds to a customer.

I’m in the midst of listening to Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence by Kate Crawford, senior principal researcher at Microsoft, professor, writer, and composer. Her analysis is expanding my awareness of the environmental and human costs of technology seldom discussed in the media, Congress, or schools.

As our engineering teacher emphasizes to her students, we need to understand the full design cycle of innovations—from their materials and manufacture to their development, energy use, and disposal—not just the flashy capabilities in the middle that garner media attention and make us happy. Many students express passionate viewpoints about addressing climate change and protecting the environment. Yet I’m not sure how many have considered the environmental impact of their smartphone or those server farms that power tools like ChatGPT.

There’s also truth to the adage if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. What are the costs to us and our students if we grow reliant on free versions of tools like ChatGPT? Are the benefits worth the risks? How will our school answer these questions? How will other high schools or colleges? How will our larger society?

“The AI you are using now is the worse AI you will ever use,” Mollick asserts.

Let that sink in for a minute.

It already feels like wizardry. What’s next?

At a retirement celebration last Friday, one of the retirees shared a story from the early years of our school. Several new teachers had been hired to serve the growing student body. When faculty arrived for the first teacher workday, the director asked everyone to board a yellow school bus. They then rode south for miles and miles, not knowing where they were headed or why, eventually pulling into the parking lot of a school in Dinwiddie County almost an hour later.

This commute, he pointed out, is one that some of our students make every day to attend our school. Your job, he said, meeting the gaze of every teacher sitting on those green vinyl seats in the sweltering August heat, is to make sure that it’s worth it. Every day.

Teenagers don’t endure that kind of commute to learn historiography, AP Spanish, or math modeling. They make it because there are people at the other end of that bus ride who look forward to seeing them, who believe they can learn, and who want them to fulfill their dreams.

Generative AI may change a lot of things, but it won’t change that.

Here’s a poem for your pocket until the next post: “These Days” by Matthew Thorburn.

The point about the source material that is used to train an AI is on point. A few years ago (after I left the place), Amazon admitted that its recruiting system based on machine learning was biased towards males it) were males. This Reuters article is a good explanation of what and how: https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1MK0AG